Radio

In college I fell in love with radio while working for WBRU. I worked at WDRE, WNEW, MTV Radio Network and joined the NPR family in 2007.

Currently I host the public radio show WNYC’s ALL OF IT with ALISON STEWART.

Television

Lena Waithe Explains Her Writing Process for “Queen & Slim”

I began my career at MTV NEWS where I won a Peabody Award for our political coverage “Choose or Lose.”

Over the next two decades, I reported for CBS News, ABC News, MSNBC/NBC News, and PBS Newshour.

Moderator

As a moderator, I love engaging with a live audience. I work with The Atlantic, host the book club GET LIT with the NYPL, and frequently moderate panels at 92Y, The Connecticut Forum, The Moth, and Symphony Space.

Books

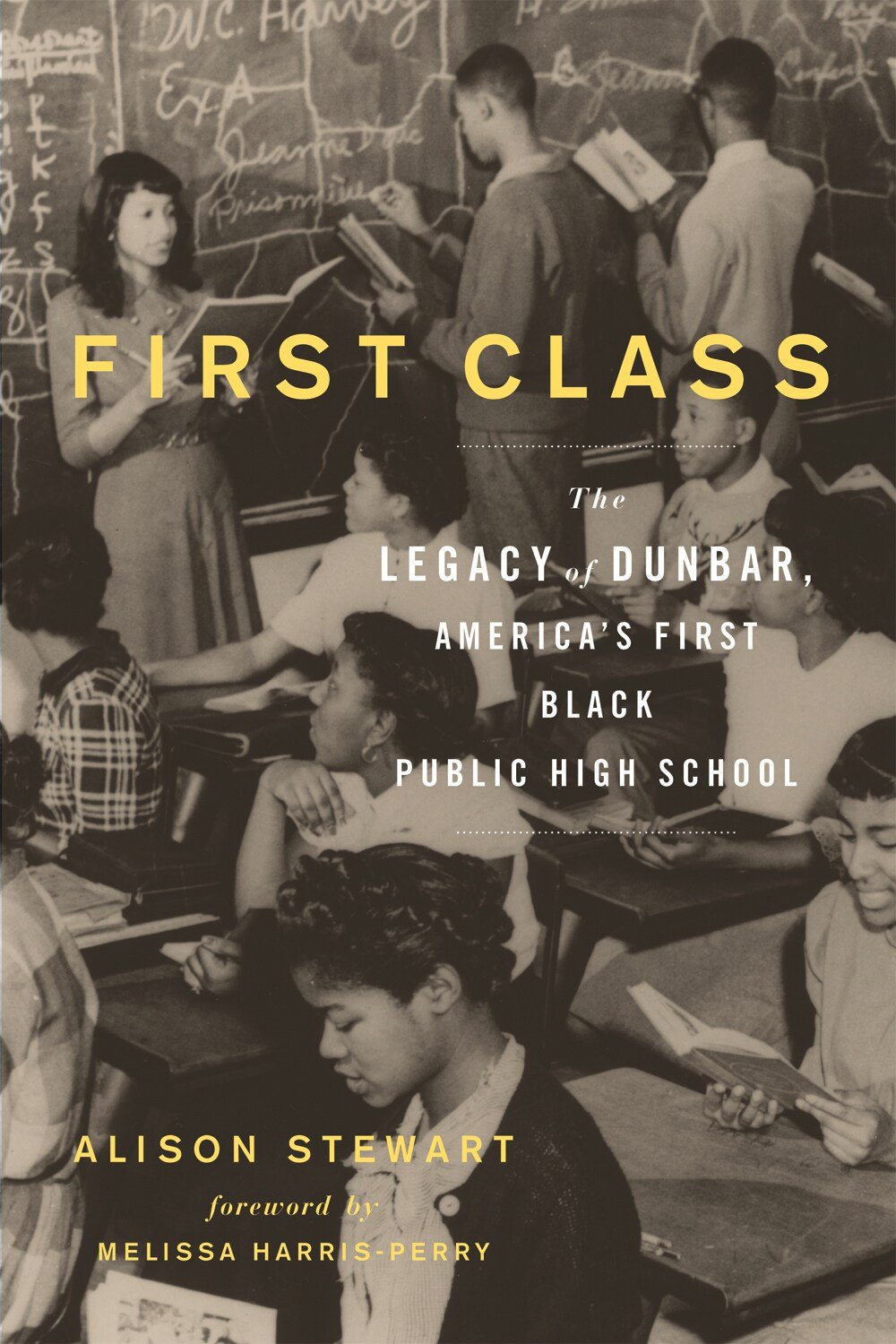

FIRST CLASS:

The Legacy of Dunbar,

America’s First Black Public High School

First Class tells the extraordinary history of the first black public high school in the United States, from its humble beginnings in a church basement during Reconstruction, to its pinnacle as an academic powerhouse rivaling …

More

JUNK:

Digging Through

America’s Love Affair With Stuff

Junk details Stewart’s journey into the country’s basements, closets and garages as she attempts to better understand why Americans can’t seem to keep their stuff under control. Stewart looks closely at how people define their junk by …

More